On one of my recent visits to Atlas Trading in the Bo-Kaap, Cape Town, a sign for Mecca Mebos on one of the shelves caught my attention. For me, Mebos is synonymous with the Cape and its dried fruit culture. On closer inspection the packet read, “Dried Apricot Paste”. The ingredients indicated on the pack included apricots, sugar, and olive oil. I was not sure why it was described as mebos, because it was not mebos as I know it.

Dried fruit producers offer mebos in different forms. These vary from the round disks, sticks, flakes, slices, to squares. Normally they are natural flavoured or sugared. The sugar tends to disguise the salty sour taste of the mebos. For me, it is a way of sweetening the experience to capture a broader audience.

What tempted me in Atlas Trading, was a small jar of mebos dip. It turned out to be a versatile dip. It had the flavour of mebos but with a spicy edge. I found the dip great for snacks and I prefer it to sweet chilli sauce. One can even use it in a marinade for a leg of pork or a roast chicken.

The name mebos is said to originate from the Japanese word umeboshi and comes from the Prunus Mume, known in Japanese as “ume”. The Prunus Mume is often translated as “Asian plum”, but this fruit is closely related to the apricot. Umeboshi is a brined, fermented sun-dried Asian plum/apricot.

During his travels at the Cape of Good Hope from 1772 to 1775, Carl Peter Thurnberg encountered mebos and compared it with the practice of drying fruit in Japan. In 1862 Lady Duff-Gordon in her letters from the Cape recorded buying mebos. On 15 April 1862 she writes, “I have bought some Cape confeyt’; apricots, salted and then sugared, called ‘mebos’—delicious! Also pickled peaches, ‘chistnee’, and quince jelly.” I can agree with Lady Duff-Gordon. I am sure it was as delicious then as it is now.

In “The story of an African Farm”, written by Olive Schreiner under the pseudonym Ralph Iron and published in 1883, Bonaparte Blenkins, the confidence trickster in the story, illustrated what a liar is by telling the story of a boy from Short Market Street, Cape Town. The boy was sent to buy meiboss (mebos). The boy came back concealing from his mother how many pieces he had bought.

“ “Here, Sampson,” said his mother, “go and

buy sixpence of meiboss from the Malay round the corner.”

“When he came back she said: “How much have

you got?”

“Five,” he said.

He was afraid if he said six and a half

she’d ask for some. And, my friends, that was a lie. The half of a meiboss

stuck in his throat and he died and was buried. And where did the soul of that

little liar go to, my friends? It went to the lake of fire and brimstone.” “

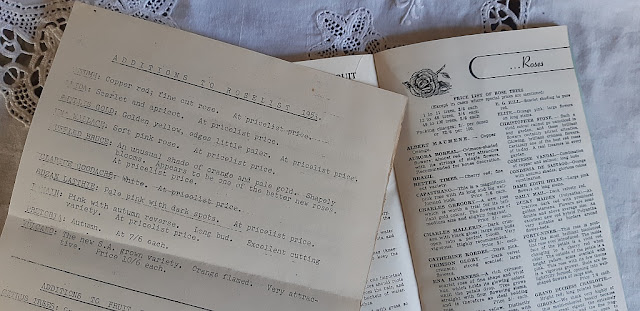

In the cookbook by Hildagonda J Duckitt, Hilda’s where is it of recipes, first published in 1891, I found the earliest recipe for the making of mebos.

|

| Hildagonda Duckitt's recipe for Mebos |

In “In Search of South Africa”, published in 1948, H. V. Morton writes, ”Mebos is not common. Here again we have something that came to the Cape from the Far East. Some believe that the word is derived from the Arabic mushmush, an apricot, but others, and this is more likely, from umeboshi, a Japanese word given to preserved plums. Mebos is made of ripe apricots, dried, salted, and sugared, and the taste is an acquired one, for it belongs definitely to that “sweet and sour” order so palatable to the Chinese. People brought up in China tell me that plums salted and sugared like mebos are still popular there, and it is fairly certain that this unusual sweetmeat came to South Africa in early times by way of the Dutch East India Company’s factories in China and Japan.”

“Daar kom tant

Alie, tant Alie, tant Alie,

daar kom tant

Alie, tant Alie om die

draai.

En tant Miena

kook stroop van die mebos-konfyt,

van die

Wellingtonse suiker teen ‘n trippens

die pond,

en tant Miena

kook stroop van die mebos-konfyt,

van die

Wellingtonse suiker teen ‘n trippens

die pond.”

|

| Apricot blossoms in the orchard |

I might be tempted to try the mebos drink, but I will pass on the vape fluid. Buying the mebos dip has inspired me to explore the culinary possibilities of mebos, but I am quite happy to sit back and enjoy this tangy salted snack just as it is.

Sources:

Letters from the Cape (1861-62), Lady Duff-Gordon, Published 1925

The story of an African Farm, Olive

Schreiner, Published 1883

Hilda’s where is it of recipes, Hildagonda

Duckitt, First Published 1891

Social Life at the Cape, C.G. Botha,

Published 1926

In Search of South Africa, H.V.Morton,

Published 1948